The Idolatry of Possibility: A Catholic Critique of the Silicon Valley Complex

Analogical Metaphysics, Digital Abstraction, and the Recovery of Christian Relation

Introduction: Theology, Digitality, and the Question of Relation

This essay, in the classical sense of an attempt, is a sustained reflection on the intersection of theology and digitality. It is thus a sustained attempt within the genre of writing that is theology and culture. It arises from the conviction that our time is marked not merely by new technologies, but by a new metaphysical atmosphere—one in which possibility reigns as the highest good, and actuality is increasingly treated as a limitation to be overcome. The digital, far from being a neutral tool or external medium, expresses a deeper structure, a logos, a mode of being. It is a metaphysics of possibility: flexible, disembodied, fluid, and abstract. What this essay seeks to explore is how this logic subtly but profoundly reshapes our relational understanding of truth, of culture, of humanity, and ultimately, of God.

There is a presumption at work in this reflection, namely, that something about digitality is new—but not new in the absolute sense. Possibility is as old as creation itself. Indeed, the seed of potentiality is present already in the earliest chapters of Genesis, where the temptation to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is not a neutral fact, but a latent possibility that, when made actual, fractures the harmony of creation. The idolisation of potential, the extraction of possibility from the structure of creation and its elevation above being itself, is an ancient temptation—one now reborn in the structures of digital culture.

This essay thus belongs within a larger theological and philosophical tradition—one that stretches from Athens and Jerusalem through Augustine and Aquinas, and into our own uncertain age. It is an essay in relational ontology, concerned with the relation between possibility and actuality, nature and grace, finitude and infinitude, time and eternity, thought and being. These form what we might call the canon of binaries that shape the West’s deepest metaphysical commitments. Theology finds its home within these binaries not by collapsing them (univocal), nor by absolutising their difference (equivocal), but by sustaining them through analogy—a mode of relation that avoids both the flattening of univocity and the chasm of equivocity.

Indeed, one of the central arguments of this piece is that the kind of relationality that matters—the kind that saves—must be analogical. There are other modes of relation: contradiction, paradox, negation, dialectic. But analogical relation preserves order without hierarchy, distinction without division, communion without confusion. It is the logic of participation, the logic of maior dissimilitudo—a greater dissimilarity that nonetheless gestures toward likeness; likeness with an even greater dissimilarity. It is this logic that governs the relation between Creator and creature, and therefore the logic by which any theology of culture must be framed.

To this end, I have been deeply influenced by the thought of Erich Przywara. Indeed, we might say he serves as one of my masters in this effort—alongside the Angelic Doctor, Thomas Aquinas. Przywara’s metaphysical vision of the analogia entis, or analogy of being, shapes much of what follows. For Przywara, analogy is not merely a theological principle; it is a rhythm, a formal structure of thought—in and beyond—that governs the very relation between God and creation. It finds its grounding in the Fourth Lateran Council’s declaration that "between the Creator and the creature, no similarity can be expressed without implying an even greater dissimilarity." This is the principle of maior dissimilitudo: that all likeness to God is always shadowed by an even greater unlikeness. (“Inter creatorem et creaturam non potest tanta similitudo notari, quin inter eos maior sit dissimilitudo notanda”)

What this means is that relation itself must be held in tension—not collapsed into identity, nor dissolved into infinite distance. Analogy sustains this tension. It is the logic of participation, the mode by which the finite shares in the infinite without confusion or conflation. It is a metaphysics of humility, of distance filled with resonance, and of likeness haunted by mystery. For Przywara, as for Aquinas, analogy is not the enemy of clarity but the condition of reverent speech about God. And in an age increasingly allergic to limits and seduced by univocal immediacy—especially in digital culture—this analogical framework provides not only a theological grammar but a spiritual medicine.

In recovering this analogical imagination, thinking with Przywara in relation to our time, we are not proposing an escape from technology, nor a moralistic screed against the digital. Rather, we are attempting to discern how digitality—like any dimension of culture—can be sanctified, drawn into the orbit of grace, and integrated into a vision of the good. This essay is an invitation to think carefully, theologically, and relationally about how we live in an age where computing has become ubiquitous, where the digital is no longer a tool we use but the very environment in which we live, move, and have our being.

But we must not allow ourselves to live and move and have our being in digitality. That would be to construct a new golden calf, to fashion a new idol out of pixels and possibility. Rather, we must pass through the digital, just as we pass through every age, every structure, every form of materiality—not to remain there, but to arrive at what transcends it: the ever greater, the God who is beyond all being yet nearer to us than we are to ourselves. Semper maior.

What follows, then, is a threefold meditation. In Part I, we examine how the metaphysics of possibility underwrites the technological imperative that governs our cultural imagination. In Part II, we diagnose how digitality manifests this imperative in an ex-carnational logic that threatens to sever us from the very conditions of human flourishing. And in Part III, we propose a path forward: an analogical metaphysics that honours both possibility and actuality, rooted in the Trinitarian and incarnational logic of Christian faith. This final part offers not only critique but also hope: a call to live faithfully in the onlife condition, as stewards of form, relation, and glory.

In nomine Domini incipiamus.

Part I: Possibility as Technological Imperative

In an age marked by accelerating innovation and technocratic hubris, we are increasingly ensnared in what might be called the Silicon Valley Complex: a metaphysical, material, socio-political, and cultural vision in which the possible is not merely potential but imperative. This complex is not simply the sum of its engineers, investors, and platforms, but a comprehensive worldview—one that fuses knowledge with production, being with manipulation, and nature with artifice. It has, in a very real sense, become our new catechism.

Within this paradigm, nature is no longer conceived as a given order to be received, interpreted, and reverenced. Rather, it is regarded as a raw datum, an artifact-in-waiting, a pliable machine subject to the instrumentality of engineering. Knowledge, accordingly, becomes not contemplative but constructive—what we know is what we can do. The true is what works; the real is what is feasible; the natural is what is possible. And in this shift lies a profound theological and philosophical displacement.

To say that nature is a kind of machine is to say that knowledge of nature is essentially engineering. And if the truth of this knowledge is defined not by conformity to being but by technical possibility, then the metaphysical horizon shifts from actuality to potentiality. The very grammar of reality is rewritten: what is, is what could be made. Truth, once understood as correspondence with being (adaequatio rei et intellectus), becomes redefined in functional terms—as utility, efficacy, feasibility.

This inversion is not without precedent. As Pope Benedict XVI (then Joseph Ratzinger) noted in his Introduction to Christianity, the modern shift in epistemology—from truth as being to truth as making—marks a decisive turn in the Western imagination. Truth becomes verum quia factum—true because made. Francis Bacon openly championed this transformation, equating knowledge with power and proposing that the measure of truth lies in its products. Heidegger, for all his critique of technology, echoes this shift in his notion of aletheia, the disclosive unveiling of being, which subtly privileges the temporal and the possible over the eternal and the actual.

The result is a metaphysics in which possibility becomes primary, and limitations are viewed not as intrinsic structures of being but as obstacles to be overcome. The technological imperative—what can be done, must be done—is thus not merely a cultural attitude but a logical consequence of this metaphysical posture. From within the technological paradigm, to resist this imperative is to appear irrational, even immoral. For reason itself, once yoked to production and progress, demands transgression of every given boundary.

But here, the exception becomes the rule. If what is natural is what is possible, then those cases which transgress current limitations come to define what nature is. Norms are no longer grounded in a shared telos or intelligible order but in the extremities of what might be. This is why the Silicon Valley Complex—understood not merely as a geographical region but as a civilisational ethos—functions as a kind of secular eschatology. It promises salvation through innovation, redemption through engineering, and meaning through optimisation.

And yet, behind this promethean vision lies a deep forgetting. The conflation of techne and logos, of making and knowing, occludes the ancient and Christian understanding of truth as something received, not fabricated; as a gift, not a product. The Catholic tradition, particularly in the metaphysical synthesis of Aquinas, sees being not as the outcome of potentiality but as actus purus—pure act. The real is what has been given in the act of creation, not what might be manufactured through acts of will.

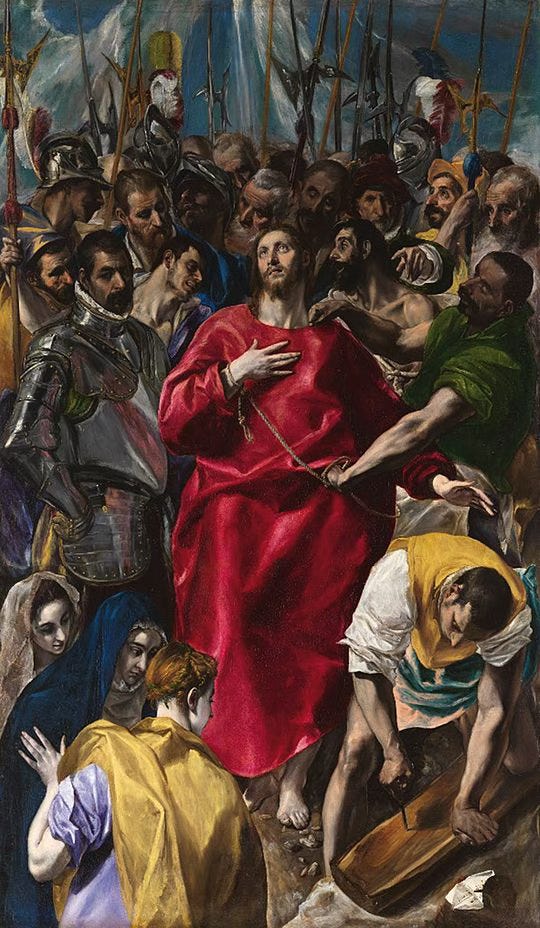

This metaphysical difference is no mere abstraction. It is the fault line between a culture of reverence and one of conquest, between a civilisation that contemplates the order of creation and one that seeks to refashion it according to its own image. The idolatry of our age is not golden calves or marble statues, but the worship of potential, the enthronement of possibility, and the deification of progress. It is a technological Gnosticism, a salvific vision that rejects the givenness of the world in favour of its remaking.

Part II: Digitality as Ex-Carnational Logic

The digital age has not merely accelerated the technological paradigm—it has instantiated its very logic. Digitality is not simply a technological advancement, but a metaphysical schema. It does not only change what we can do; it alters what we think is. To inhabit the digital world is to enter a space structured not by actuality, but by the primacy of possibility.

At its core, digitality functions through code—binary representations of presence and absence, 1 and 0. In this duality, reality is no longer fluid and continuous (as in the analog), but discretised and abstract. It is representation severed from material constraint. Here, being hovers in a state of suspension—what has not yet become, but could be at any moment. This is the metaphysics of virtuality: a theatre of pure potential.

Before the code is compiled, before the pixel is rendered, before the algorithm is activated, digital structures exist as possibilities—not-yet-actual, but always available. This condition—of always being on the verge of manifestation—bears uncanny resemblance to the Gnostic and Neoplatonic conception of perfection as unmanifest. The true, in this vision, is that which is formless, infinite, unbounded—whereas form and determinacy are seen as limitation, even degradation.

In this way, the digital revives the ancient inversion of classical metaphysics. Where the Greeks (and the Christian tradition following them) saw the perfection of being in form and actuality, the Gnostic tradition saw perfection in the unformed—and viewed manifestation, particularity, and materiality as a fall. Thus, in digital logic, the refusal to be anything definite becomes a kind of metaphysical virtue. Fluidity, editability, potentiality—these become the hallmarks of the real.

Digital technologies, particularly artificial intelligence, data avatars, and virtual spaces, tempt us with the fantasy of disembodiment—of escaping the constraints of biology, history, and place. In this, the digital does not simply reflect Gnostic tendencies; it institutionalises them. Our cultural movement toward digitality is thus not merely economic or technological—it is theological. It presupposes a soteriology of escape and a cosmology of possibility.

But Catholic metaphysics insists upon the priority of form, of limit, of being as act. To be is to be something—hoc aliquid—to have received a nature. God is not pure potential but pure act. Creation is not a mistake to be corrected through digital transcendence, but a gift to be received, reverenced, and sanctified.

Thus, the digital world, if unmoored from sacramental and incarnational theology, risks becoming a metaphysical parody: a space of infinite becoming with no being; of possibilities with no ends; of communication without communion. It threatens to dissolve the very categories of truth, identity, and embodiment upon which human flourishing depends. We no longer believe lies about being. We simply cease to care whether being is at all. This is the new disorder: metaphysical bullshit.

Part III: Analogical Metaphysics and the Onlife Vocation

If the first two parts of this reflection diagnose the metaphysical structure of our present age—the dominance of possibility, the rise of digital abstraction, and the suppression of form—this third part gestures toward a way forward: an analogical and relational ontology grounded in Trinitarian theology.

At its core, theology is not merely propositional but relational. It is the study of God precisely as God relates—to Godself in the triune life, and to creation in the act of love. The doctrine of the Trinity reveals that relation is not accidental to being, but constitutive. The divine persons are not substances in relation, but relations as persons. And in the Incarnation, this divine relationality descends into form, into history, into matter.

The Christian claim is thus neither that the divine is beyond relation, nor that all is relation in a flat, networked sense—but that relation, analogy, is the very logic of participation in being. The analogical imagination allows us to hold together the canon of binaries that structure Western thought: God and world, nature and grace, time and eternity, body and soul, actuality and possibility. It neither collapses one into the other nor severs them beyond repair. It maintains the both/and that is at the heart of Catholic metaphysics.

This matters not merely at the speculative level, but in the concrete way we live. A metaphysics of analogy leads to a vocation of balance: contemplation and action, prayer and work, form and openness. Monastic life, for example, embodies this analogical rhythm: ora et labora, time consecrated to divine relation. Thinkers such as Sebastian Morello rightly affirm this participatory ontology, though their approach to the digital often risks demonising the medium rather than discerning its logic. Pace Dreher, digitality is not inherently demonic; rather, it must be drawn into a higher order, disciplined by form, and transfigured by grace.

Indeed, many of the theological debates—between Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option, Tracy Rowland’s cultural Thomism, and Protestant critics of Hellenisation—revolve around differing views on the relation between theology and culture. Whether one sees culture as fallen and to be escaped, or as a medium of grace to be sanctified, will shape one’s liturgy, politics, and posture toward the world. (Note bene: This is, in the truest sense, an essay: not a finished doctrine, but a faithful attempt to think—fides quaerens intellectum.)

But in the face of the Silicon Valley Complex, where capital, code, and narrative are woven into a new catechism of possibility, we must retrieve the Christian grammar of actuality, limit, and form. We must remember that culture is not merely made, but received; that history is not merely backward, but meaningful; that technology is not ultimate, but penultimate to invoke Tillich.

This is the promise of the onlife vocation: to live neither in nostalgic retreat nor in utopian abstraction, but in the analogical middle. To be creatures, not gods; stewards, not sovereigns. And to remember that our highest calling is not to endlessly choose, but to freely respond to the gift of being.

In recovering analogical metaphysics, we recover the splendour of the real—the radiance of the world as icon, not idol. And in doing so, we prepare ourselves not merely to critique the technological age, but to sanctify it.

Conclusion: The Harmony of Distinctions

We stand at the precipice of a cultural and metaphysical turning point—one in which the gravity of possibility threatens to undo the very fabric of form. The temptation is not new. It is the perennial idolatry: to confuse what can be with what ought to be, to collapse the sacred distinction between potentiality and actuality, and to forget that being is a gift, not a project.

Our age has taken this confusion and rendered it structural. It is embedded in the architecture of our machines, in the grammar of our algorithms, in the ethos of our education, and even in the liturgy of our daily lives. The digital does not merely reflect a metaphysics—it enforces one. It does not merely express a cultural mood—it amplifies and canonises it. And that metaphysics, as we have shown, is one that privileges disembodiment over incarnation, abstraction over form, and fluidity over fidelity.

Against this backdrop, the analogical imagination emerges not as an optional philosophy, but as a necessary theology. It is the only frame capacious enough to hold the canon of binaries—God and world, time and eternity, body and soul, possibility and actuality—without collapsing them into indistinction or alienating them into irrelevance. It is the harmony of distinctions, not their erasure, that preserves meaning.

Christianity, in its most metaphysically mature form, teaches us not to resolve tension through reduction, but to dwell within it through relation. The Incarnation is the ultimate refusal of collapse: God remains God, and yet becomes man. The cross is the axis mundi where finitude meets infinity, where form receives the fullness of divinity without being destroyed by it. This is not dialectic. It is not contradiction. It is analogy—and it is the logic of love.

Thus, the calling before us is not to escape the digital, nor to sanctify it uncritically, but to pass through it analogically, neither enthroning it as saviour nor scapegoating it as demon. We must become interpreters, not just users—interpreters of the age, of its technologies, of its metaphysical drift. And we must do so with both clarity and compassion, with the confidence that form is not our enemy, but the condition of all communion.

To live analogically is to live liturgically—to live as if the world means something because it has been spoken into being by a Word who is Love. It is to see each thing as a sign that points beyond itself, not as raw material for self-invention. And it is to resist the false infinite of digital possibility by returning to the true Infinite, whose glory is revealed not in escape, but in embrace.

In the end, the canon of binaries is not a prison but a hymn. And only by singing each part in relation to the others can we find our home again in the harmony of creation.